FDA Announces Recall on 6,000 M&M Candies Due to Undeclared Allergens: A Comprehensive Guide for Consumers

WASHINGTON — The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has announced a significant recall affecting approximately 6,000 units of repackaged M&M’s candies, sparking concern among consumers and highlighting the critical importance of accurate food labeling. The recall, initiated by Beacon Promotions Inc., stems from a labeling error that failed to disclose the presence of major allergens—specifically milk, soy, and peanuts—on the packaging of promotional candy packets.

While the recall was voluntarily initiated by the company on January 26, 2026, the FDA escalated the situation on February 4, 2026, by classifying it as a Class II recall. This classification indicates a situation where the use of or exposure to a violative product may cause temporary or medically reversible adverse health consequences, though the probability of serious adverse health consequences is remote.

For the millions of Americans living with food allergies, however, such labeling oversights are far more than administrative errors—they represent a direct threat to health and safety. This extensive report details the specifics of the recall, the “why” behind the move, how to identify affected products, and the broader implications for food safety in the promotional products industry.

The Recall at a Glance: What Went Wrong?

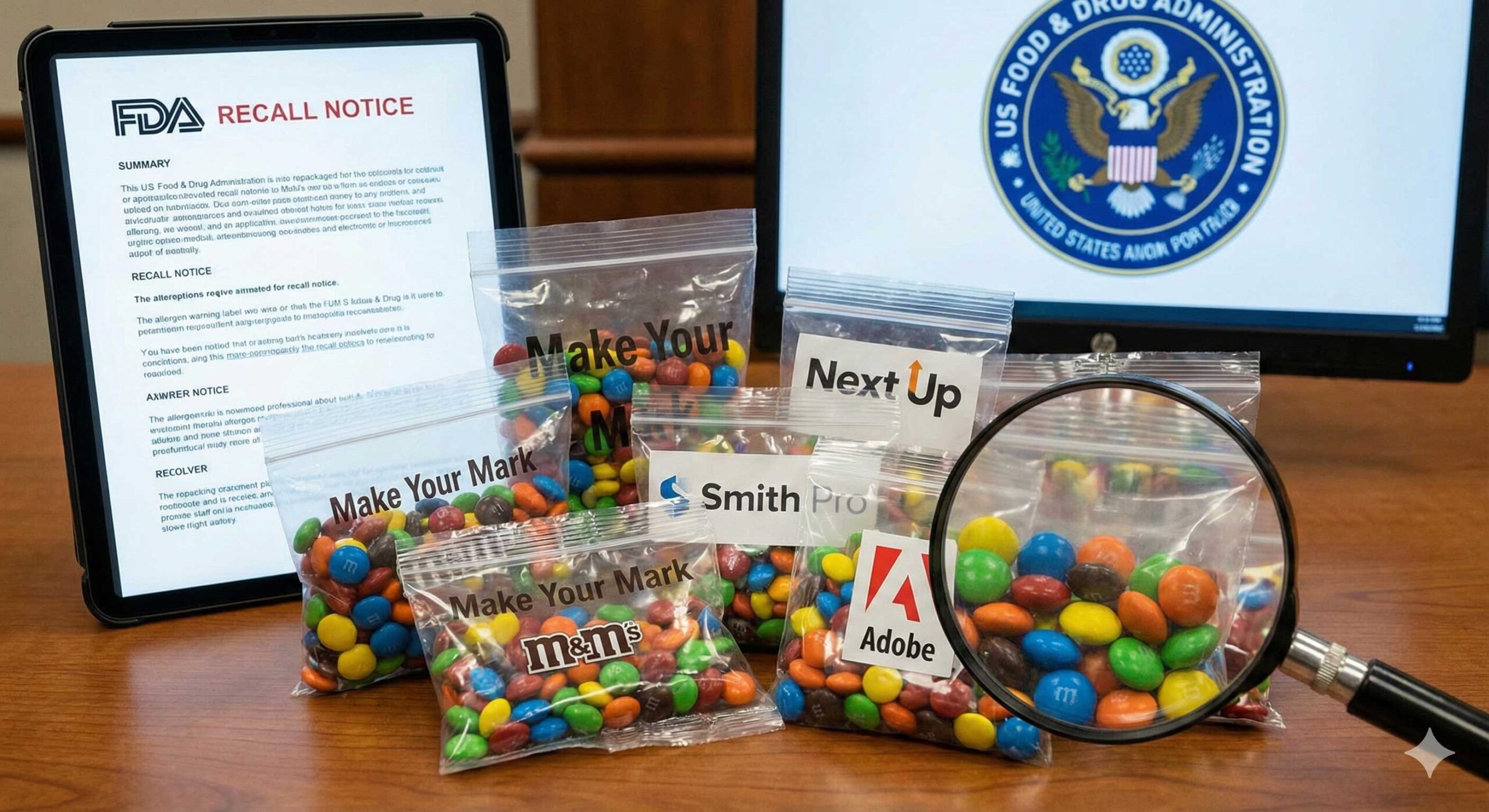

The recall centers on a specific batch of M&M’s candies that were not sold in standard retail packaging found at grocery stores or gas stations. Instead, these candies were repackaged by Beacon Promotions Inc., a company specializing in branded merchandise. The candies were distributed in packaging labeled with various promotional company names, intended for corporate events, trade shows, and giveaways.

The critical failure occurred during the repackaging process. While the candies inside the packets were genuine M&M’s—which naturally contain milk and soy (and peanuts for the peanut variety)—the new promotional packaging failed to transfer the mandatory allergen warning labels found on the original manufacturer’s packaging.

Under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) and the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act (FALCPA), any food product containing a “major food allergen” must explicitly declare that allergen on its label. By omitting this information, the repackaged candies became “misbranded” under federal law, necessitating immediate removal from the market.

Detailed Product Identification: Are You Affected?

Beacon Promotions Inc. has issued a detailed list of the specific lots affected. Consumers who have recently received M&M’s at corporate events, conferences, or as part of promotional gift baskets are urged to check their products immediately.

The recall encompasses two distinct categories of products:

1. Repackaged Peanut M&M’s

These products pose the highest risk due to the severity of peanut allergies.

- Packaging Label: “Make Your Mark”

- Item Number: BB471BG

- Lot Number: M1823200

- Best By Date: April 30, 2026

- Quantity: Approximately 541 units

2. Repackaged Regular M&M’s

These contain milk and soy, which are also major allergens.

- Packaging Label: Various promotional logos including “Next Up,” “Smith Pro,” “Jaxport” (Jacksonville Port Authority), “Climax Molybdenum” (A Freeport-McMoRan Company), “University of Maryland School of Public Policy,” “Liberty University Environmental Health & Safety,” “Subaru,” “Morgan” (Construction Manager/Design Builder), “Adobe,” “Xfinity,” “Fundermax Interiors,” “White Cup,” “Acadia Commercial,” “Aviagen,” and “ORG Expo.”

- Item Number: BB458BG

- Affected Lot Numbers & Expiry Dates:

- Lot L450ARCLV03: Best By 12/1/2025

- Lot L502FLHKP01: Best By 1/1/2026

- Lot L523CMHKP01: Best By 6/30/2026

- Lot L537GMHKP01: Best By 9/1/2026

- Quantity: Approximately 5,788 units

Geographic Distribution

The reach of this recall is extensive, covering 20 states across the continental United States. The affected products were distributed to:

- Alabama

- Arizona

- California

- Florida

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Minnesota

- New York

- North Carolina

- Ohio

- Pennsylvania

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Virginia

- Washington

- Wisconsin

Because these items were distributed as promotional materials, they may have traveled further than the initial distribution points. Attendees of conferences in these states may have brought the candy back to other regions, making vigilance necessary nationwide.

The “Why” Behind the Move: Understanding FDA Classifications

The FDA’s involvement in this recall highlights the rigorous nature of U.S. food safety laws. When the FDA classified this recall as Class II on February 4, 2026, it provided a risk assessment that helps consumers understand the severity of the threat.

- Class I Recall: This is the most serious category, reserved for situations where there is a reasonable probability that the use of the product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death (e.g., E. coli contamination or undeclared peanuts in a product not expected to contain nuts).

- Class II Recall: This classification, applied to the current M&M recall, suggests that exposure may cause temporary or medically reversible adverse health consequences, or that the probability of serious adverse health consequences is remote.

- Class III Recall: This is used for products that are unlikely to cause any adverse health reaction but violate FDA labeling or manufacturing laws (e.g., a minor defect in packaging or a lack of English labeling on a non-critical item).

While “Class II” sounds less alarming than “Class I,” it is not a green light for complacency. For individuals with severe sensitivities to milk, soy, or peanuts, the consequences of consuming undeclared allergens can escalate quickly from “temporary” to life-threatening anaphylaxis. The “remote” probability of serious injury cited in the definition applies to the general population, not necessarily the specific high-risk group of allergic individuals.

The Danger of Undeclared Allergens

To the average consumer, a missing label on a packet of chocolate might seem like a minor technicality. However, undeclared allergens remain the leading cause of food recalls in the United States, and for good reason.

Peanut Allergies:

Peanut allergies are among the most common and dangerous food allergies, particularly in children. Exposure to even minute amounts of peanut protein can trigger anaphylaxis, a severe, whole-body allergic reaction that can impair breathing, cause a dramatic drop in blood pressure, and lead to unconsciousness or death. For a peanut-allergic person, eating a “Make Your Mark” packet of M&M’s thinking it is plain chocolate could be fatal.

Milk Allergies:

While often confused with lactose intolerance (a digestive issue), a milk allergy is an immune system reaction to the proteins in milk (casein and whey). It is one of the most common allergies in children. Reactions can range from hives and vomiting to bloody stools and anaphylaxis.

Soy Allergies:

Soy is a pervasive ingredient in processed foods, often hidden in lecithin or flavorings. While soy allergies are generally less severe than peanut allergies, they can still cause significant distress, including skin redness, digestive issues, and respiratory problems.

The danger in this specific recall lies in the context. M&M’s are a widely recognized candy, and most consumers know they contain chocolate (milk) and potentially peanuts. However, when packaging is altered—rebranded with a corporate logo or a university name—the consumer’s mental connection to the original manufacturer’s ingredients list can be severed. A consumer might assume the product is a generic candy or fail to realize it is a peanut variety if the visual cues of the classic yellow M&M’s bag are missing.

The Role of Repackaging in Food Safety

This recall shines a spotlight on a niche but significant sector of the food industry: promotional repackaging.

Companies like Beacon Promotions Inc. serve a vital role in corporate marketing. They take bulk products—pens, notebooks, and yes, candy—and customize them to carry a client’s brand. When dealing with non-food items, a misprint is a branding failure. When dealing with food, a misprint is a public health hazard.

The process typically involves purchasing bulk quantities of a product (like M&M’s) and transferring them into smaller, custom-printed bags. During this transfer, the “chain of custody” for information is broken. The original master case from Mars Wrigley (the maker of M&M’s) carries all FDA-mandated labeling. If the secondary repacker does not meticulously transcribe this information onto the thousands of smaller individual packets, they violate federal law.

This incident serves as a wake-up call for the promotional products industry. It underscores the necessity of robust Quality Assurance (QA) protocols that treat food items with the same regulatory rigor as pharmaceutical repackaging. Every “Best By” date, lot number, and ingredient list must survive the transition from bulk to individual packaging.

What Consumers Should Do

If you possess one of the recalled packets, the FDA and Beacon Promotions advise a specific course of action depending on your health status.

1. For Individuals with Allergies:

If you or anyone in your household has an allergy to milk, soy, or peanuts, do not consume this product. The risk is simply not worth it. Even if you believe the candy looks like “regular” chocolate, cross-contamination in a repackaging facility or a mix-up in product types is possible.

- Disposal: The safest route is to throw the candy away in a secure trash bin where children or pets cannot access it.

- Return: If you received the item from a company or organization, you may contact them to inform them of the recall, although since these were likely free promotional items, a monetary refund is unlikely.

2. For Individuals Without Allergies:

Technically, the candy itself is not contaminated with pathogens like Salmonella or Listeria. It is the label that is defective. If you are certain that you have no sensitivity to milk, soy, or peanuts, the product is safe to eat. However, out of an abundance of caution, many consumers choose to discard recalled products regardless of the reason to avoid any confusion.

3. Verification:

Check the back of the promotional packet for a lot code. It is usually printed in small black ink near the seal. Compare this number against the list provided above (e.g., L450ARCLV03). If the numbers match, the product is part of the recall.

Broader Implications: A Trend in Recalls

The Beacon Promotions recall is part of a larger trend of increased vigilance regarding food allergens. In recent years, the FDA has ramped up enforcement of FALCPA and the newer FASTER Act (which declared sesame the 9th major allergen).

According to FDA data, labeling errors regarding allergens are consistently the number one reason for food recalls in the U.S., surpassing bacterial contamination. This suggests that while food manufacturing sanitation has improved, the administrative and logistical management of packaging has struggled to keep pace with the complexity of supply chains.

This recall also highlights the responsibility of “secondary” food handlers. While Mars Wrigley manufactured the candy, they are not the recalling firm. The responsibility falls on the entity that altered the packaging. This distinction is crucial for consumers who might otherwise blame the primary brand for an error committed downstream.

Corporate Responsibility and Response

Beacon Promotions Inc., based in Eagan, Minnesota, took the correct first step by initiating the recall voluntarily on January 26. This proactive measure is standard industry practice once an error is discovered, aimed at mitigating risk before the FDA mandates action.

However, the delay between distribution and recall means many of these units have likely already been consumed. The nature of promotional items—often eaten immediately at a trade show booth or tossed into a conference bag and forgotten—makes retrieval difficult. Unlike a grocery store that can pull items from shelves, there is no central point of sale to lock down.

To date, there have been no confirmed reports of adverse allergic reactions associated with these specific products. This absence of illness reports likely contributed to the Class II rather than Class I classification.

The Psychology of Promotional Food

There is a psychological element to this recall that is worth noting. When consumers buy food at a store, they are in “acquisition mode,” often checking labels for price, nutrition, and ingredients. When consumers receive free food at an event, they are in “reception mode.” The barrier to trust is lower. We tend to assume that a gift is safe.

This cognitive bias makes labeling even more critical on promotional items. A person who diligently checks labels at the supermarket might mindlessly tear open a branded packet of chocolate at a seminar, assuming that if it were dangerous, someone would have said so. The “Make Your Mark” or corporate logo effectively masks the identity of the food, turning it from a “food product” into “swag.”

Timeline of Events

- Pre-January 2026: Bulk M&M’s are purchased and repackaged by Beacon Promotions into various branded packets.

- Distribution: Products are shipped to corporate clients in 20 states for use in marketing and events.

- January 26, 2026: Beacon Promotions discovers the labeling error (likely through internal audit or a client query) and voluntarily initiates a recall.

- January 26 – February 3, 2026: The FDA reviews the firm’s recall strategy and assesses the public health risk.

- February 4, 2026: The FDA officially classifies the event as a Class II Recall, formalizing the risk level and publicizing the details to the wider media.

- February 6, 2026: Media outlets, including Mint and others, disseminate the information to the public to ensure end-users—the recipients of the swag—are aware.

Conclusion

The recall of 6,000 units of repackaged M&M’s by Beacon Promotions Inc. serves as a potent reminder of the fragility of the food supply chain’s information flow. In an era where food allergies are rising, the label on a package is not just marketing—it is a medical document.

For the 6,000 people holding these packets, the message is simple: Check the code. If you have allergies, toss it.

For the wider public and the industry, the lesson is deeper. Whether a product is sold on a shelf or handed out at a booth, the fundamental right of the consumer to know what they are eating remains paramount. As the FDA continues to monitor this recall, it stands as a testament to the system working—identifying errors, assessing risk, and communicating to the public to keep American plates (and snack bowls) safe.

Consumers with further questions are encouraged to monitor the FDA’s official recall website or contact Beacon Promotions directly for resolution. As always, when in doubt regarding food safety, the adage remains: If you can’t verify it, don’t eat it.